Git & GitHub cheat sheet

Table of contents

- Basics

- Configuration

- Repository initialization and cloning

- Checking status and history

- Staging and committing changes

- Synchronizing with the remote repository

- Branching basics, Merging branches, Merge conflicts

- Pull requests on GitHub

- Reset, Revert, Stash, Tags, Flags

.gitignore- Forks

- Rebasing

- Interactive rebasing

- Advanced Git commands

- Branch naming, Aliases, Hooks

- GitHub pages, Conclusion

Git is a distributed Version Control System (VCS) that allows us to track code changes, manage collaboration, and improve the development process. This article covers essential Git commands and explains how to leverage GitHub's pull request (PR) functionality for collaborative workflows. You don't need to memorize all the commands from this article. Treat it more like a cheat sheet because you have to learn Git through practice and real-world experience, and not only by reading.

Basics

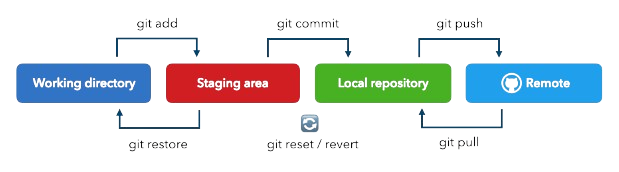

A repository is a storage space for a project, including its full version history. A local repository resides on our computer, and a remote repository is hosted on a server (e.g., GitHub), allowing for collaboration and version control across multiple users. A commit is a snapshot of the project's changes at a specific point in time, capturing the modifications made to files and providing a unique identifier for tracking the history of those changes. Branches are parallel versions of the project that allow us to work on different features or fixes independently, enabling us to merge changes back into the main codebase without disrupting the primary workflow.

When we're ready to commit certain changes, we add ("stage") them to Git's staging area using git add. The staging area holds a snapshot of these changes, preparing them for the commit. This allows us to control which changes go into each commit. The working directory is the local folder where we edit and save files. Any changes made here are untracked by Git until they are staged (into the staging area).

Configuration

git config --global user.name "Your Name" |

Setting your username for commit attribution. |

git config --global user.email "you@example.com" |

Setting your email for commit attribution. |

Repository initialization and cloning

git init |

Initializing a new Git repository in the current directory. |

git clone [repository URL] |

Cloning an existing repository, including all history and files. |

git remote add origin [repository URL] |

Linking the local repository to a remote one ("origin" refers to the default name for the remote repository, usually the one we cloned from). |

git remote -v |

Viewing all remote repositories and their URLs. |

Checking status and history

git status |

Showing the current state of the working directory and staging area. |

git log |

Displaying commit history with full details. |

git log --oneline |

Showing condensed commit history. |

git log -2 |

Showing the last two commits from history. |

git diff |

Showing unstaged changes in the working directory. |

git diff --staged |

Showing changes that have been staged (added with git add). |

git diff HEAD |

Comparing the working directory and staging area with the latest commit. |

git diff --name-only |

Listing only the names of files that have changed. |

git diff commit1Id commit2Id |

Showing changes between two specific commits. |

A diff file in Git represents the differences between two sets of files or commits. It shows which lines have been added, removed, or modified in the codebase. This output is commonly used in code reviews and patch generation, helping developers understand exactly what has changed and why. The symbols in a diff file provide clear context for each change, as listed below.

+ |

Line added in the new version. |

- |

Line removed from the previous version. |

@@ |

Hunk header showing line numbers and context of the change. |

diff --git |

Start of a new diff section showing the compared files. |

index |

Shows blob object IDs and file mode (hashes) before and after the change. |

--- |

Indicates the original file path. |

+++ |

Indicates the new file path. |

Staging and committing changes

git add [file or directory] |

Staging specific files/directories. |

git add . |

Staging all changes. |

git add -p |

Interactively choosing portions of files to stage. |

git commit -m "[message]" |

Creating a commit with a message. |

git commit |

Opening editor for a detailed commit message. |

Commit messages should answer the prompt: "If applied, this commit will …" to provide clear descriptions of code changes.

Synchronizing with the remote repository

git fetch |

Downloading remote changes without merging. |

git pull |

Fetching and merging remote changes. |

git push |

Uploading local commits to remote. |

git push origin main |

Pushing local changes to the main branch on the remote, ensuring only fast-forward updates and avoiding overriding existing changes. |

git push origin main --force |

Force pushing local changes to the main branch, overriding any conflicts on the remote (use with caution). |

git push -u origin [branch_name] |

Pushing and setting an upstream branch. |

An upstream branch is a remote branch that the local branch is tracking, allowing for easy synchronization of changes between the two. Setting an upstream branch enables us to use simplified Git commands, such as git push and git pull (without defining the branch every time).

Branching basics

git branch |

Listing local branches. |

git branch -a |

Listing all branches (local and remote). |

git branch [branch-name] |

Creating a new branch. |

git branch -d [branch-name] |

Deleting a branch (if it has been merged). |

git branch [new-branch-name] [source-branch] |

Creating a new branch from a specified source branch. |

git checkout [branch-name] |

Switching branches. |

git checkout -b [new-branch] |

Creating and switching to a new branch. |

git switch [branch-name] |

Modern command for switching branches (Git 2.23+). |

git switch -c [new-branch] |

Modern command for creating and switching to a new branch (Git 2.23+). |

git restore [file] |

Discarding working directory changes (Git 2.23+). |

git restore --staged [file] |

Unstaging changes while preserving modifications (Git 2.23+). |

Merging branches

git merge [branch-name] |

Merging a specified branch into the current branch. |

git merge --no-ff [branch-name] |

Creating a merge commit even for fast-forward merges. |

git merge --abort |

Aborting an ongoing merge. |

git pull origin main |

Pulling the latest changes from main after a pull request merge. |

Merge conflicts

A merge conflict occurs when two branches have competing changes to the same line of code or file, preventing automatic merging and requiring manual resolution.

If they arise, Git will mark the affected files. We can resolve these by editing the files, identifying conflict markers (<<<<<<<, =======, >>>>>>>), and deciding which changes to keep. Conflict markers are special annotations added to a file by Git to indicate the sections of code that are in conflict during a merge, typically showing the differing changes from each branch.

# Fetch updates from the main branch

git fetch origin main

# Switch to the main branch and merge with the feature branch

git switch main

git merge feature_branch

# Resolve conflicts manually in the files, then stage and commit the resolved files

git add [resolved_file]

git commit -m "Resolve merge conflicts in feature_branch"

Pull requests on GitHub

A pull request (PR) is a GitHub feature for proposing and discussing changes before merging them into the main branch. This is useful for code reviews and ensures better-quality code.

Creating a pull request

- Create and switch to the feature branch:

git switch -b feature-branch. - Make changes and commit them.

- Push branch:

git push -u origin feature-branch. - On GitHub:

- Navigate to the repository.

- Click "New Pull Request".

- Select branches.

- Fill the PR description using a template (if available).

- Add reviewers and labels.

PR best practices

- Keep PRs focused and reasonably sized.

- Write clear descriptions explaining:

- What changes were made?

- Why changes were needed?

- How to test the changes?

- Any related issues or dependencies?

- Respond to review comments promptly.

- Update PR with requested changes.

- Resolve conflicts when they arise.

Reviewers can annotate lines and approve or request changes. This review process ensures code quality and promotes team collaboration. As changes are requested, additional commits can be made to the branch and pushed to the PR.

Reset

git reset [file] |

Unstaging a file from the staging area without deleting changes from the working directory (the local file system). |

git reset --soft [commit] |

Moving the current branch back to a specific commit, retaining changes in the staging area for further modifications. |

git reset --hard [commit] |

Moving the current branch back to a specific commit and discarding all changes in the working directory and staging area, effectively resetting the state of the repository to that commit. |

Revert

git revert [commit] |

Creating a new commit that undoes the changes from a specified commit. |

git revert --continue |

Continuing the revert process when multiple commits are reverted, used in cases like undoing merges. |

git reset changes the repository's history by moving the branch pointer, making it useful for local changes not yet pushed. git revert is ideal for undoing specific commits without altering commit history, as it creates a new commit.

Stash

git stash |

Temporarily storing uncommitted changes in the local repository (they won't be pushed to the remote repository). |

git stash push -m "message" |

Stashing with a description. |

git stash list |

Viewing all stashes. |

git stash apply |

Applying the most recent stash while keeping it on the stash list. |

git stash pop |

Applying the most recent stash and removing it from the stash list afterwards. |

Tags

Tags are a powerful feature that allows us to mark specific points in the project history, such as releases or significant milestones. We can create a tag using the git tag -a v1.0 -m "Version 1.0" command, which creates an annotated tag with a message. Tags are useful for versioning software, making it easy to reference and retrieve specific versions of the codebase in the future.

git tag |

Listing all tags. |

git tag -a v1.0 -m "Version 1.0" |

Creating an annotated tag. |

git push origin --tags |

Pushing tags to remote. |

git tag -d [tag-name] |

Deleting a local tag. |

Flags

Flags modify command behavior or add extra functionality, customizing commands with options starting with a dash (-) or double dash (--).

-m: specifying a commit message directly in the command line.-u: staging changes only to the tracked files when usinggit add(ignoring untracked files).

.gitignore

The .gitignore file is crucial for managing which files and directories Git should ignore in our repository. By specifying patterns for files that should not be tracked, such as build artifacts, temporary files, or sensitive information, we can keep the repository clean and focused on the essential code. This helps prevent unnecessary files from cluttering the version history and ensures that sensitive data does not get accidentally shared.

Forks

A fork is a copy of a repository that allows us to freely experiment with changes without affecting the original project. This workflow is particularly useful in open-source development, where contributors don't have direct write access to the main repository. When we want to contribute to an open-source project, we have to fork the repository, which means creating a copy of the original repository under our GitHub account. This allows us to make changes, add features, or fix bugs independently without impacting the original codebase. After making our desired changes in our forked repository, we can submit a pull request to the original repository, proposing that our changes be reviewed and potentially merged into the main project. This process encourages collaboration and helps maintain the integrity of the original project while allowing contributors to experiment and innovate freely. To fork a repository on GitHub, log in to GitHub and navigate to the repository you want to fork, click the Fork button in the upper right corner, select your account if prompted, wait for the forking process to complete, access your forked repository under your GitHub account, and optionally clone your fork locally using git clone https://github.com/your-username/repository-name.git.

Rebasing (git rebase)

Rebasing is used to move or replay a sequence of commits from one base to another. This is commonly done to update a feature branch with the latest changes from the main branch while keeping a linear history.

git switch feature |

Switching to the feature branch. |

git fetch origin |

Fetching the latest changes from the remote repository. |

git rebase origin/main |

Reapplying the feature branch commits on top of the latest main branch. |

This ensures that the changes are applied on top of the most recent work from the main branch, helping to avoid unnecessary merge commits.

Example

This example fetches the latest changes from the remote repository (origin/main) and then reapplies the commits from the current local feature branch (feature) on top of it. This results in a cleaner, linear history without introducing a merge commit.

# On the feature branch

git fetch origin

git rebase origin/main

Use rebasing for local branches to keep commit history clean before merging.

Avoid rebasing public/shared branches to prevent rewriting published history.

Resolve any conflicts that arise during the rebase process and continue using git rebase --continue.

Interactive rebasing (git rebase -i)

Interactive rebasing is a powerful tool for cleaning up our commit history before sharing our code. It allows us to modify commits in various ways, including combining, editing, or removing them.

git rebase -i --root |

Starting interactive rebase from the very first (root) commit of the repository. |

git rebase -i HEAD~n |

Starting interactive rebase for the last n commits. |

git rebase -i [commit-hash] |

Rebasing interactively from a specific commit. |

git rebase --abort |

Canceling the rebase operation. |

HEAD~n refers to a specific commit in Git's history, where HEAD represents the current commit we are on, and n is a number indicating how many commits to go back from that point. For example, HEAD~1 refers to the commit just before the current one, HEAD~2 refers to two commits back, and so on.

Examples

Interactive rebase session

# Start interactive rebase

git rebase -i HEAD~5

# You'll see something like this in your editor:

pick 2231360 Add the initial login form

squash 3d4d2d1 Fix login form styling

fixup 2b504be Update login form padding

reword f7f3f6d Add form validation

edit cdd94dc Implement password reset

The pick command indicates that the commit with the specified hash should be included in the final history as is.

The squash command combines the specified commit with the previous one, allowing us to merge their changes and edit the commit message.

The fixup command also combines the specified commit with the previous one, but it does so without prompting to edit the commit message.

The reword command allows us to modify the commit message of the specified commit while keeping its changes intact.

The edit command pauses the rebase process at the specified commit, allowing us to make changes before continuing the rebase.

Splitting a commit

# During rebase, when stopped at 'edit'

git reset HEAD^

git add file1

git commit -m "First part of the split"

git add file2

git commit -m "Second part of the split"

git rebase --continue

Never rebase commits that have been pushed to public branches.

Create a backup branch before complex rebases using git branch backup-branch.

Keep commits logically grouped.

Write clear commit messages that explain the "why" not just the "what".

Test your code after completing the rebase.

Troubleshooting

git rebase --abort |

Canceling the rebase and returning to the previous state. |

git rebase --continue |

Continuing the rebase after resolving conflicts. |

git reflog |

Viewing history to recover from mistakes. |

git push --force) after rebasing can cause issues for other developers. Use git push --force-with-lease instead as a safer alternative.

A real-world problem

Suppose you are working on a branch and have made three commits: 1, 2, and 3. After testing, you realize that commits 2 and 3 introduced bugs and should not be included in the final branch. Instead of keeping the buggy changes, you want to go back to commit 1, make the correct changes, and create a new commit 4 that represents the fixed work. Using interactive rebase, you can drop commits 2 and 3, effectively removing them from the branch history. Then, apply your corrected changes and commit them as commit 4. This results in a clean history: 1 → 4, with the buggy commits completely skipped.

Advanced Git commands

git cherry-pick [commit] |

Selectively applying a specific commit to the current branch, useful for incorporating a fix without merging the entire branch (merging only a selected commit). |

git bisect |

Performing a binary search through commits to identify where a bug was introduced by marking commits as "good" or "bad." |

git blame [file] |

Viewing who last modified each line of a file, useful for tracking changes and understanding code history. |

git reflog |

Viewing the log of all changes made to Git references, allowing recovery of commits even if they aren’t in the current history. |

git worktree |

Working on multiple branches simultaneously in separate directories, enabling parallel development without losing changes. |

git filter-branch |

Rewriting commit history by applying filters to branches, useful for removing sensitive data or cleaning up the history. |

git merge --squash [branch] |

Merging changes from another branch as a single commit, ideal for maintaining a clean history before merging to the main branch. |

git submodule |

Including one Git repository within another, helping manage dependencies like shared libraries or components in projects. |

git submodule foreach [command] |

Running a Git command in each submodule, streamlining updates or operations across all submodules. |

Branch naming

Use consistent prefixes:

feature/- for new features.bugfix/- for bug fixes.hotfix/- for critical fixes.release/- for release branches.support/- for maintenance branches.

Aliases

Creating Git aliases can significantly improve our workflow by allowing us to shorten frequently used commands. For example, we can set an alias for the checkout command with git config --global alias.co checkout. This means we can simply type git co instead of git checkout. Using aliases can save time and reduce the likelihood of errors when typing long commands.

We can set up useful aliases in .gitconfig:

[alias]

co = checkout

br = branch

ci = commit

st = status

unstage = reset HEAD --

last = log -1 HEAD

*reset HEAD -- - the two dashes indicate that what comes after is a file path.

Hooks

Git hooks are scripts that Git runs before or after specific events in the workflow, enabling automation and policy enforcement within repositories. Located in the .git/hooks directory, these customizable scripts can validate commit messages, run tests before pushes, or trigger deployments after merges, helping teams maintain code quality and improve their development processes.

GitHub pages

GitHub Pages is a service provided by GitHub that allows us to host websites directly from our GitHub repositories. It is an easy and free way to publish static websites, such as personal portfolios, blogs, or project documentation. It supports HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, and it integrates seamlessly with GitHub repositories, meaning that any changes made to the repository automatically update the live website. We can choose to host our site from the root of the repository or a specific branch. Additionally, GitHub Pages provides custom domain support, allowing us to link our domains to our hosted websites.

Conclusion

Understanding these Git commands and workflows is crucial for effective collaboration in software development. Regular practice and consistent use of Git will help maintain a clean repository history and smooth team collaboration. Always remember to pull before pushing, keep commits focused, and write clear commit messages for better maintainability.